By James F. Landers, originally published 2003

Peering east over the Anza-Borrego I see dull brown and dusty khaki in shimmering waves over the barren desert and parched badlands, chalk-white sand and thorny cholla cactus. The inhospitable character of this place is evident: hot, dry, prickly.

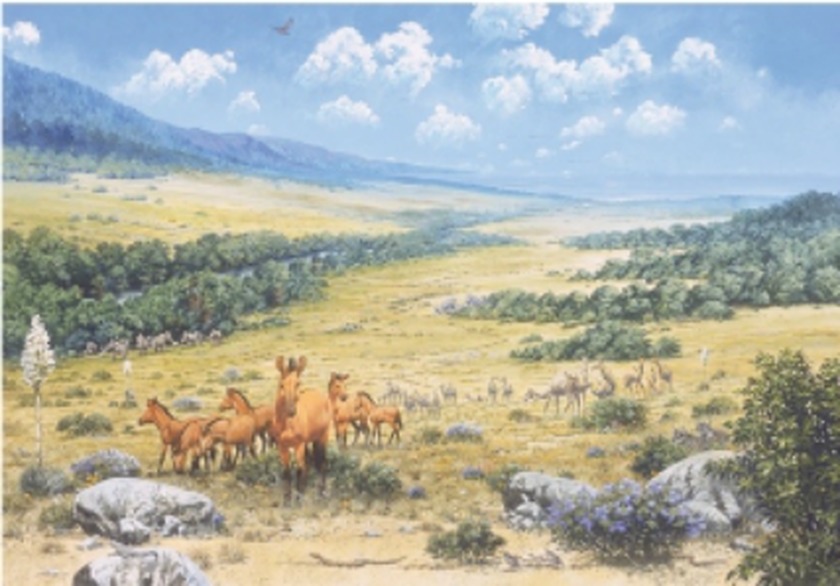

In the same place, however, George Jefferson sees a broad, grassy savannah latticed by gentle streams and strewn with woodlands of willow and cottonwood, an arid, subtropical world populated by grazing herds of mammoth elephants, zebra-like horses, camels, llamas, giant tortoises, ground sloths, short-faced and spectacled bears, wolves, saber-toothed cats and much more. No one living has ever seen these animals, but that is what their million-year-old bones say to paleontologists like Jefferson. His vision of this past world teeming with marvelous life, where now there is only withered wasteland, is part of what drives his organization of paleo volunteers in their quest to learn how to locate, identify, collect and preserve the fossil bones, and the wealth of valuable information associated with them in the earth.

On a Friday in March of 2002, that vision led a group of us to the resting place of a young mammoth interred perhaps 800,000 years ago in the Borrego badlands.

Friday We Found a Mammoth

Sixteen Anza-Borrego Desert State Park® (ABDSP) paleo volunteers set forth from Borrego Springs, east of San Diego, that Friday morning in 4-wheel-drive trucks and SUVs, for the Badlands. The field trip was one of several scheduled routinely each month between curation and lab work; our leader was 60-year-old staff paleontologist George Jefferson – who in the office is never far from a thermos of coffee, and in the field favors dress shirts open at the collar under his full gray beard, and a field lunch of canned sardines. I was issued a digital camera and instructed to accompany and bear witness. Our objective was to survey some areas not yet visited, blank areas on Jefferson's maps of fossil sites plotted with coordinates from global positioning satellites (GPS).

Bouncing along for several miles after leaving the highway, we passed dunes and low hills rutted by dirt bikes and dune buggies, crossed into a state park area closed to vehicular traffic, then entered narrow washes that lead into still more narrow arroyos, until we were inching along between vertical sand embankments barely far enough apart to pass a jeep. Finally we arrived at a point beyond which we would go by foot. The hiking equipment, surveying instruments, and digging tools were unpacked, heads counted and teams assigned, and water and whistles checked, then we were off.

Single-file we climbed to the top of a narrow, reddish-brown sandstone ridge, and along precarious crests on foot-wide trails of reddish powder ground from the parched crust by the boots of past teams of paleo volunteers. All around us the earth was cut into deep, wrinkled arroyos by streams of white sand, and ridge after folded ridge drifting off into a haze of windblown desert dust called to mind imagery of desolate moonscapes.

We descended from the ridges and tracked into a labyrinth of arroyos too deep to see the sun. I lost all sense of direction, but many of these volunteers know their way around these badlands as well as they know how to get from their refrigerator to their front porch at home. The teams split up; one scrambled up the nearest wash, the other up the adjacent wash.

Before long a whistle blew out of the nearest wash, calling for photo and GPS support. Volunteer Richard Caputo had found a fragment of an unidentified scapula. Shortly afterwards, another whistle blew further up the same wash where volunteer Melinda Trizinsky had found two horse teeth, weathered square-inch blocks about three inches long, just beyond a scatter of bone fragments flowing down a nearby slope. Spirits began to rise noticeably – the excitement was catching, and people began burbling about "horse tooth city," and how they'd not seen any specimens at all the last time out.

Another whistle blew, this time from the direction of an adjacent wash. And it blew again, and again. Someone was really excited now. Photo and GPS support trooped back down out and over to the wash, past a bone scatter beside the streambed, over a fall of sandstone blocks across the channel, and into a narrow passage in places sixty or so feet high and only a few feet wide. At intervals under the sandy ledge beside the dry stream, volunteers gingerly brushed dust from protruding bone fragments. Further up the wash volunteer Scott Heid, a tall and slender import to California from Pennsylvania, stood before his discovery: the tusk of a small mammoth, embedded in the sandstone wall above the streambed. A chunk of tusk just under four inches in diameter protruded from the wall about five inches, and just behind it a length of the same-diameter tusk was exposed in the wall for about sixteen inches before disappearing into the ledge, where the rest of the specimen may possibly be buried

Bouncing along for several miles after leaving the highway, we passed dunes and low hills rutted by dirt bikes and dune buggies, crossed into a state park area closed to vehicular traffic, then entered narrow washes that lead into still more narrow arroyos, until we were inching along between vertical sand embankments barely far enough apart to pass a jeep. Finally we arrived at a point beyond which we would go by foot. The hiking equipment, surveying instruments, and digging tools were unpacked, heads counted and teams assigned, and water and whistles checked, then we were off.

Single-file we climbed to the top of a narrow, reddish-brown sandstone ridge, and along precarious crests on foot-wide trails of reddish powder ground from the parched crust by the boots of past teams of paleo volunteers. All around us the earth was cut into deep, wrinkled arroyos by streams of white sand, and ridge after folded ridge drifting off into a haze of windblown desert dust called to mind imagery of desolate moonscapes.

We descended from the ridges and tracked into a labyrinth of arroyos too deep to see the sun. I lost all sense of direction, but many of these volunteers know their way around these badlands as well as they know how to get from their refrigerator to their front porch at home. The teams split up; one scrambled up the nearest wash, the other up the adjacent wash.

Before long a whistle blew out of the nearest wash, calling for photo and GPS support. Volunteer Richard Caputo had found a fragment of an unidentified scapula. Shortly afterwards, another whistle blew further up the same wash where volunteer Melinda Trizinsky had found two horse teeth, weathered square-inch blocks about three inches long, just beyond a scatter of bone fragments flowing down a nearby slope. Spirits began to rise noticeably – the excitement was catching, and people began burbling about "horse tooth city," and how they'd not seen any specimens at all the last time out.

Another whistle blew, this time from the direction of an adjacent wash. And it blew again, and again. Someone was really excited now. Photo and GPS support trooped back down out and over to the wash, past a bone scatter beside the streambed, over a fall of sandstone blocks across the channel, and into a narrow passage in places sixty or so feet high and only a few feet wide. At intervals under the sandy ledge beside the dry stream, volunteers gingerly brushed dust from protruding bone fragments. Further up the wash volunteer Scott Heid, a tall and slender import to California from Pennsylvania, stood before his discovery: the tusk of a small mammoth, embedded in the sandstone wall above the streambed. A chunk of tusk just under four inches in diameter protruded from the wall about five inches, and just behind it a length of the same-diameter tusk was exposed in the wall for about sixteen inches before disappearing into the ledge, where the rest of the specimen may possibly be buried

Scott had followed a pale gray-green layer of silty sandstone flecked with tiny carbonate nodules. His recent training in a volunteer paleo class led him to wonder if the greenish layer was formed in a swampy pond, stream or lakebed. Such places often accumulate bones washed into a stream course. He came upon a curious conglomeration of white particles arrayed across a ledge, which turned out to be concretions of skull fragments, and when he turned back down the wash he saw the tusk.

This mammoth’s remains were discovered in the spring. Groups of volunteers have been making the trek to the site most Fridays to complete the painstaking process of removing rock from around the tusks.

This mammoth’s remains were discovered in the spring. Groups of volunteers have been making the trek to the site most Fridays to complete the painstaking process of removing rock from around the tusks.

At one of those treks, the volunteers listened as Jefferson described how the mammoth probably looked and what might have happened to its bones. The animal was probably the size of a modern day female elephant, 25 or younger and weighing 6000 to 7000 pounds, he said. Chances are it died just to the south of where the tusks now lie. Because the skull and tusks were the heaviest bones in its body, they would have been less likely to be carried away by a stream. “We know downstream is in that direction,” Jefferson said, pointing north. “So we’re not expecting anything that way,” he said, pointing the other way.

Jefferson described how he thinks the tusks were situated under a rock and how he wanted to remove the material around them.

Jefferson described how he thinks the tusks were situated under a rock and how he wanted to remove the material around them.

Norbert Sanders aimed a drill at the wall above the tusks and bored holes in the sandstone in a honeycomb pattern. Over the succeeding weeks, teams of volunteers worked at the site, pulling the wall apart with a chisel and delicately brushing away debris from around the tusks.

Later a plaster jacket would be constructed and the tusks would be removed from the field encased in a net under a helicopter.

Later a plaster jacket would be constructed and the tusks would be removed from the field encased in a net under a helicopter.

James Lande is the author of Yang Shen: God of the West Book I http://oldchinabooks.com/yangshen/

and also Yankee Mandarin http://oldchinabooks.com/yankeemandarin/

and also Yankee Mandarin http://oldchinabooks.com/yankeemandarin/